Lucifer's Hammer book review

Humanity is about to go the way of the dinosaur. A mass extinction event is cruising through space, and its name is Hamner/Brown. When the apocalypse arrives, how will humanity deal with the fallout? Water vaporised, endless salt-water rain, earthquakes…

Hide your kids, hide your wife. The comet is coming.

Spoilers ahead!

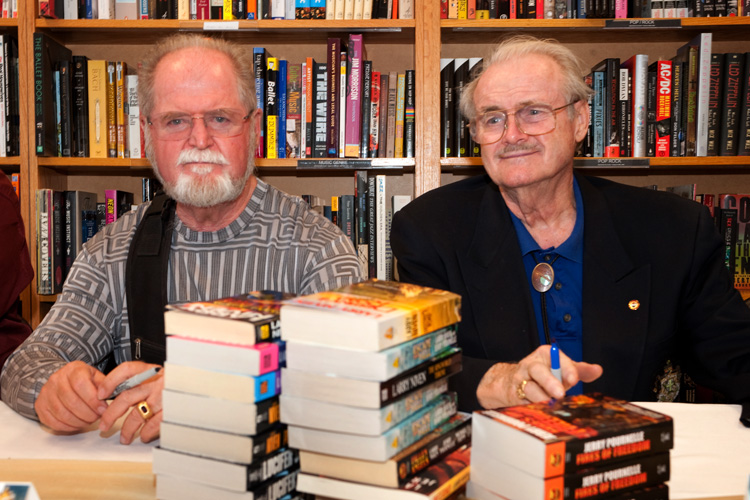

Lucifer’s Hammer is a classic work of science fiction and was nominated for the Hugo and Locus awards for Best Novel. The dynamic writing duo of Jerry Pournelle and Larry Niven published it in 1977, and along with their similar end-of-the-world novel Footfall, set the benchmark for end-of-the-world stories. A vast cast of characters, unconnected at first, are brought together by the comet and the havoc it wreaks.

The story starts with Richie Rich amateur astronomer Tim Hamner discovering a comet — but don’t worry, the chances of it hitting earth are like a million to one. No, wait, a thousand to one. No, wait… The first act goes on to introduce a dizzying array of characters. The main members of the cast are Tim Hamner (see above), documentary filmmaker Harvey Randall, and United States senator Arthur Jellison. The early pages are littered with soap opera moments that don’t equate to much — Barry Price is sleeping with his secretary, for example, never really has much meaning or consequence. These soap opera moments are similar to the ones found in Footfall. Their purpose, I assume, is to add a little spice to the long opening setup.

Speaking of the similarities to Footfall, Mark Czescu is very similar to Footfall’s Hairy Red. Both are bikers, not winning at life, who sing for their supper. It’s a bit weird that two similar characters would feature in two similar books.

But then the comet strikes, and the book kicks into high gear. The Hammer, as the comet is known, spares no one — and only those able to scramble to higher ground survive the tsunamis and other destruction. Shortly after it hits, we witness China and Russia enter a game of “who can nuke who first”. Things aren’t looking too good.

The book is interspersed with poet snippets that describe the great destruction of The Hammer, but for the most part, the story is set in California. Nearly every character introduced early on has a critical role in the latter stages of the book — unlike Footfall, which often introduced characters that faded out of the story.

The book’s final third focuses on a small township attempting to survive the aftermath. Our heroes face tough ethical choices — and eventually decide to set up barricades to keep desperate “refugees” out of their town. Food is scarce, as the characters ultimately agree they can “only be as ethical as they can afford to be”. This is a bit different from the more liberal Hollywood disaster stories, in which there is usually an impassioned speech declaring that we must help everyone wherever possible, despite the dire situation at hand. Lucifer’s Hammer takes a grimmer view of how humanity would behave during the apocalypse.

And so we get to the inevitable part where we discuss the dated aspects of the book. Yep, Lucifer’s Hammer was written in 1977, and its treatment of women, race and environmentalism is not in line with modern thinking.

There are quite a few female characters (which is an improvement over The Mote In God’s Eye, at least), but they’re nearly always defined by their relationship to a male character. Maureen is Senator Jellison’s daughter. Dolores is Barry Price’s love interest. Marie Vance is Harvey’s neighbour. The only exception is the Russian doctor and kosmonaut Leonilla Malik, but she is part of the supporting cast. The book often makes reference to “women’s liberation” — a somewhat dated phrase — which I suppose was a big deal back in the 70s.

Although the book has a few black characters (Rick Delanty, Hook and Alim Nasoor), the authors did choose to have a bunch of black people wind up as crazy cannibals by the third act. Okay, there are white cannibals too, but many of them are black. Alim Nasoor is also a murderer and a thief, which means the only non-white character who is also a decent bloke is astronaut Rick Delanty. There are no Asian characters, no Indians, no Australians… The book is not outright racist (and I certainly don’t believe Niven and Pournelle harbour such attitudes, even in secret), but by today’s woke standards, it could have benefited from a more balanced cast of characters.

The book also has a dated view of environmentalism. Nuclear power is good, and those pesky environmentalists are always carrying on about CFCs in aerosol cans! Today, climate change is generally regarded as the single biggest threat to humanity — so to read a book that treats environmentalists as wackos is a bit worrying.

Whether the above prevents one from enjoying the story is down to the individual. The book is 45 years old, and although I’m a pretty woke kind of person, I’m willing to forgive it for the most part. It’s never outright racist, sexist or anti-environment, but it does take a more conservative stance than the current, mainstream point of view. I found it a bit annoying more than anything, as the dated aspects sometimes jerked me out of the exciting story world.

All that being said, the book otherwise holds up remarkably well, considering its age. Niven and Pournelle are such a powerful writing team — the story is paced beautifully (despite being double the length of a typical novel), and the excitement builds and builds as the story progresses. Countless movies such as 2012, The Day After Tomorrow and Deep Impact owe a huge debt to Lucifer’s Hammer. Without books like this, I doubt we’d have those movies.

Overall, Lucifer’s Hammer was a gripping read by the best in the business. Yes, some aspects of it are frustratingly dated, but if you can look past those faults, it’s an absolute ripping yarn, and a worthy addition to anyone’s sci-fi book collection.